You sometimes don’t always realise how deep we have come from, when it comes to food supply. It is so normal to walk into a supermarket 7 days/week and pick out what you want to eat. Over a century ago, this was completely different. The 19th century, the century of the industrial revolution, initiated the change in our food. People moved to the cities and increasingly worked in factories. A city like Berlin was among the first metropolises, growing from 170,000 in 1800 to 1.9 million people in 1900 (Lummel, 2002), i.e. adding over 170,000 people a year!!! Food had to be brought in from outside the cities. Markets sprang up, where producers offered their fresh goods daily, there were street vendors who delivered products to homes, and central market halls emerged, which served as storage and transit of fresh goods.

People came out of the tradition of self-sufficiency, also in Berlin every family initially had a vegetable garden, a pig, but soon this was no longer possible and fresh produce had to be driven into the city daily. Technology and industrial processing were deployed to feed a city population. Berlin, as a city itself, took the initiative to build a huge abattoir with a central livestock market on the outskirts of the city, including a rail link to deliver fresh meat into the city daily (Lummel, 2002). In those days, transport distance and the state of the roads played a big role in what products people could feed on. People originally ate a lot of brew (from flour), bread and potatoes, all low-fragile products. People ate preserved products, the first canned goods, dried meat, as all of these had a long shelf life and refrigeration in the houses was lacking. Cheese was possible, milk was difficult.

German historian Hans-Jürgen Teuteberg (1929-2015) describes the changes in nutrition in Germany from 1850 to 1980 and what was consumed per capita. In his studies, you get a general picture of what was slowly changing, but also a picture between the different classes in society, and the differences between urban and rural areas.

From hunger to stable food supply late 19e century

Especially as late as the beginning of the 19e century, there were very regular food shortages and even famine once every 4 years (Ellerbrock, 2002). Inadequate infrastructure, feudal farming systems, low soil fertility meant that there were years with crop failures and famine. This was also true in the Netherlands. The farmer and writer Harm Tiesing describes for the province of Drenthe, how the sandy soils became depleted at the end of the 19e century, ‘and the rye fields yielded no more grain than the farmers sowed in springtime’. Phosphate deficiency was the main factor that marked the end of the 1,000-year-old heather-deep litter agricultural system. Pleistocene sandy soils covered large parts of Europe, and everywhere the sandy soil was depleted. In all parts of Europe, where people did not live on clay soils or peat bogs, things were shabby. People were decrepit and skinny. The first artificial fertilisers, the insight born of knowledge of the chemistry of plant growth (Von Liebig, 1865), brought crops back to normal.

At the start of the industrial age, much of the population lived mostly vegetarian by necessity. Knits of flour (grain), potatoes and few animal products characterised this one-sided, daily diet. Vincent van Gogh painted the famous ‘potato eaters’ in Nuenen in Brabant (1885). Many were malnourished. Nutrition was one-sided and from today’s understanding, there were shortages of protein, vitamins and minerals. Food processing and processing slowly shifted the diet of urban workers: more calories became available, the amount of animal products increased, as did the consumption of animal fats. Food became more digestible, but also fuller in taste and smell. Of course, a big difference remained between the more luxurious food of the upper classes in society and the working class.

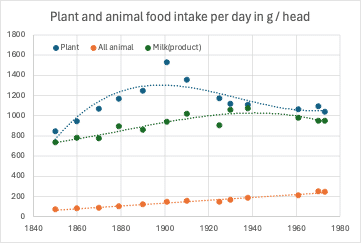

Fig. 1 The diet in Germany, divided into plant, dairy and animal products (meat, eggs, fish), (in grams per person per day).

Figure 1 shows, that plant-based food intake reaches its maximum in the early 20e century and then gradually starts to decline. Assuming, that plant-based foods in terms of bread and cereals provided the bulk of food and belly filling, it seems, that hunger did not exist from then on (early 20e century: 1900-1910). Consumption of meat, fish and eggs shows a straightforward, steady increase from 1850 to 1975. Every 10 years, over 14 g more meat is eaten, rising from 70 g (1850) to 250 g (1975) per day. Milk and milk products also rise, but level off even before WW-II. After that, milk consumption is more likely to decline slightly (from 1940 to 1975).

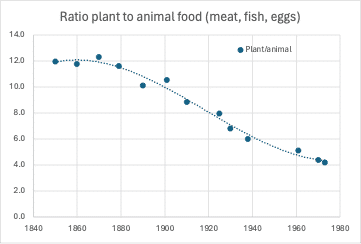

Fig 2. The relationship between plant and animal products (meat, fish, eggs) is getting tighter

Up to 1880, the ratio of plant-to-animal food is about 12. In terms of weight, 12x as much plant food is eaten compared to meat, fish and eggs combined. However, after 1880, there is a fairly constant decline, so that this ratio drops to 4 in 1970 (Figure 2).

Wheat, rye, pulses, potatoes

The statistics worked out by Van Teuteberg allow us to see, how the share of different products in the daily diet shifts. In the 19th century, rye is the most important grain. Rye is known as a grain, which still wants to grow even on poorer soils. On the sandy soils in the Dutch province Drenthe mentioned above, there was ‘eternal rye cultivation’. Wheat could only thrive on richer soils along the coast, such as the Zeeland wheat and Groningen cereal fields (both sea clay soils).

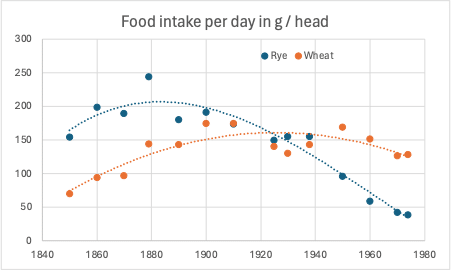

Fig 3. The amount of rye gradually decreases and is taken over by the consumption of wheat.

At the end of the 19th century, rye consumption peaks before increasingly disappearing from our diet. Rye bread is replaced by the more luxurious wheat bread (Figure 3). This is due to two reasons: trade comes into play and large ships transport wheat from the US to Europe. Furthermore, due to the use of fertilisers (first Phosphate (P) and Potassium (K)) and after WW-I also nitrogen (N), wheat can also be grown on poorer soils, not only in clay and loam areas.

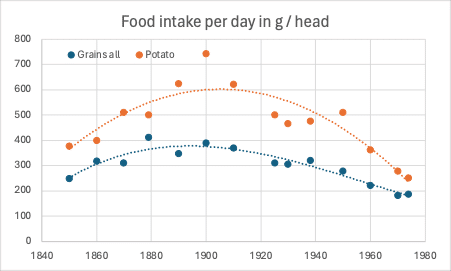

Fig 4. The largest amounts of daily calories came from potatoes and all cereals combined until 1910.

The total amount of cereals (wheat, rye, oats, barley and rice combined) peaked as early as 1890, the amount of potatoes a little later (around 1910). The periods of ‘real famine’ are over and people can get fed up with these plant-based foods (Figure 4).

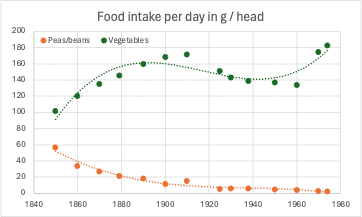

Fig 5. Legumes disappeared, vegetables came

To still achieve a reasonable protein share in the vegetable diet before 1910, legumes (beans, peas) were eaten. They formed an important part of the (mainly) vegetarian diet of the poorest in the population. However, they largely disappeared after 1920 (Figure 5). Consumption of vegetables rises sharply until around 1910, before declining somewhat. Something changes after 1960, when the availability of vegetables, probably due to imports, improves rapidly.

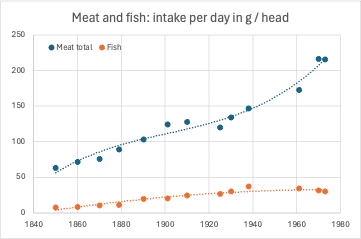

Fig 6. Meat consumption shows a steady increase, while fish consumption stabilises and remains limited in size

Ample meat for each – an egg a day

In 1850, people eat an average of around 70 grams of meat, fish plus eggs per day. Fish consumption stabilises at around 30 grams after WW-II, however, meat consumption gradually continues to rise to around 150 grams before WW-II to increase sharply further in the post-war period. By the mid-1970s, German people were eating over 200 grams of meat and meat products per day (Figure 6).

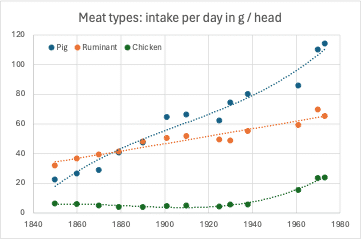

Fig 7. Pork and (especially) beef are major sources of animal protein, however, lean chicken meat experiences a surge after WW-II.

Consumption of beef (including veal and sheep/goat meat) rises very gradually but consistently. Pork too, but much more strongly than beef. Chicken makes its appearance especially after WW-II (Figure 7).

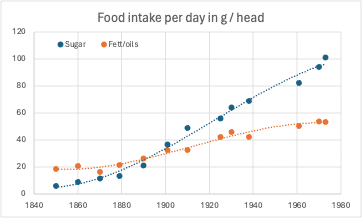

Fig 8. Fat (margarine, oil and animal fat) and sugar consumption constantly increases in the 20e century

Fat consumption rises gradually in the 20th century, before levelling off in the 1970s. In contrast, sugar consumption rises from about 10 grams per day (1880s) to 100 grams per day by the mid-1970s (Figure 8).

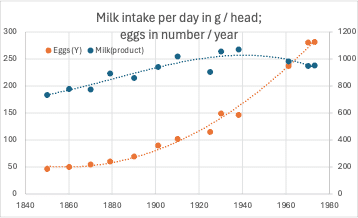

Fig 9. Consumption of milk and milk products stabilises even before WW-II, while egg consumption rises to almost 1 egg per day in the 1970s

Eggs were originally expensive. In the late 19th century, people ate about 50 eggs a year, say 1 egg a week. After that, consumption increased annually to about 280 eggs a year, say almost 6 eggs a week. Milk and milk products gradually increased from over 700g per day to peak at around 1050g per day until WW-II. After that, milk consumption stabilised and slowly started to decline (Figure 9). It is not clear what part of this weight can be traced to drinking milk and what part to processed milk products.

Milk consumption and income

Milk consumption was an average for the entire German population. There were big differences between the ranks and classes in the population, what people could afford. The poorest, and largest part of the population had a much lower consumption of mainly animal products.

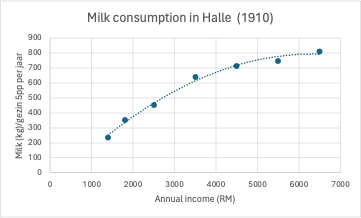

In 1910, the correlation between milk consumption and income was investigated in the city of Halle (Figure 10). It is clear, that while the poorest workers could still hardly afford milk (-products), more milk was consumed in the richer parts of the city population. Consumption levelled off, at roughly 800 litres/family/year, equivalent to almost 0.5 litres per person per day. In contrast, the poorest families drank only ¼ of this.

When prosperity increased, the consumption of milk initially increased somewhat, but much less than that of meat, sugar and fats. Most milk probably went to the children in the family. Drinking milk was mostly considered a foodstuff for children, the sick and the weakened.

Fig 10. Milk consumption in the town of Halle at the beginning of the 20e century in relation to household income (Van Teuteberg, 1981).

The poorer working-class population with meagre incomes spent proportionally a much higher share of their income on food (about 50%), than the higher income classes. If one was richer, then one spent more money on better food and on more animal products, however within income as a total one spent less (at least about 22%).

Other stats from historical work (Lummel, 2002) also show, how the wealthy upper class spent money on wine, champagne, liqueurs and imported beer from Bavarian monasteries in addition to their better food, while the middle class indulged in liqueur, wheat beer and imported beer. The lowest income class, however, relied on cheap gin from potatoes, sweet brown beer or 2nd rank beer (Dünnbier = thin beer) with lower alcohol contents. The differences applied not only to alcoholic drinks but also to hot drinks (type of coffee), the fish people ate, as well as meat and sausages.

Milk in urban and rural areas

Until the late 19th century, you could get even better milk in the countryside than in the city. It was more readily available and fresher. Cows and goats provided a daily supply of raw milk for children in the villages. It was different in the ever-growing cities and where supply was over long distances. Infant mortality was high in the emerging industrial cities, where more than 20 per cent of infants died, and the milk arriving in the cities was often not to be trusted for several reasons. Milk in cities was often already old, partially soured, poorly refrigerated and/or adulterated by admixture with the craziest products. At that time, milk was a difficult and fragile foodstuff, because you actually had to be able to chill it immediately and deliver it cool to the house door within 12-24 hours of milking. At first, this did not work at all and therefore you were better off with raw milk in the countryside than in the cities. There, there were short distances and a daily fresh supply.

Photo. Bolle Meierei in Berlin (D), (Source Wikipedia)

Often the convinced entrepreneurs initiated something new. Carl Bolle (1832-1910) started selling milk from his own cows on his city farm within Berlin (Creamery with Milkgarden in 1879), but a few years later he built the first large milk factory (1887), from which pasteurised milk was distributed throughout Berlin. Milk was brought in by rail from the surrounding area over distances of up to 200km. Instead of sterilising the milk, Bolle milk was heated no further than 70o C. Raw milk (as Vorzugsmilch) was also part of their programme, alongside yoghurt, cottage cheese and butter. Daily, more than 250 peddlers drove the milk through part of the city. Pasteurisation of drinking milk was not made compulsory throughout Germany until 1930; Bolle was ahead of its time.

Conclusion

- Until 1910, food scarcity and even regular famine were common. Much food consisted of plant products, especially potatoes and cereals. The amount of meat was still modest, and the consumption quantity and composition (plant-animal-milk) was strongly determined by the class to which one belonged.

- Improvements in agriculture, imports of grains from the US, and technology (refrigeration, transport, heat, assembly line) made processing sensitive products like meat and milk increasingly accessible to many. Not insignificant (since 1860) is the discovery of fertilisers, which allowed people to grow grass and cereals even on depleted sandy soils.

- Cereals, potatoes and pulses were gradually replaced by rising meat consumption, first mainly pig meat, after WW-II also chicken. Meat consumption tripled in about 100 years.

- Milk and milk products have always been a part of the daily diet, and while consumption increased until before WW-II, it gradually began to decline after WW-II. Drinking milk was initially considered a beverage for children, elderly people, the weak and sick.

Literature

- Ellerbrock, K. P. (2002). „Die Lebensmittelindustrie als Vorreiter der modernen Marktwirtschaft “. Nahrungskultur. Essen und Trinken im Wandel. In: Der Bürger im Staat, Bd, 52, 247-251.

- Lummel, P. (2002). Von der Hungersnot zum Beginn modernen Massenkonsums—Berlins nimmersatter Riesenbauch—Die Lebensmittelversorgung einer werdenden Weltstadt. Nahrungskultur. Essen und Trinken im Wandel. In: Der Bürger im Staat, Bd, 52, 252-258.

- Teuteberg, H. J. (1979). Der Verzehr von Nahrungsmitteln in Deutschland pro Kopf und Jahr seit Beginn der Industrialisierung (1850-1975). Versuch einer quantitativen Lang-Zeitanalyse. Archiv fur Sozialgeschichte, 19, 331-388.

- Teuteberg, H. J. (1981). Beginnings of the modern milk age in Germany. Food in perspective.