A new concept is emerging, a new awareness about the actual price and the invisible costs for the future and generations after us on earth. German TV featured a contribution on this topic in relation to our food consumption (Planet Wissen). What do you pay for now and what don’t you see in the litre of milk, a tomato in winter or a pound of organic meat? What costs are passed on?

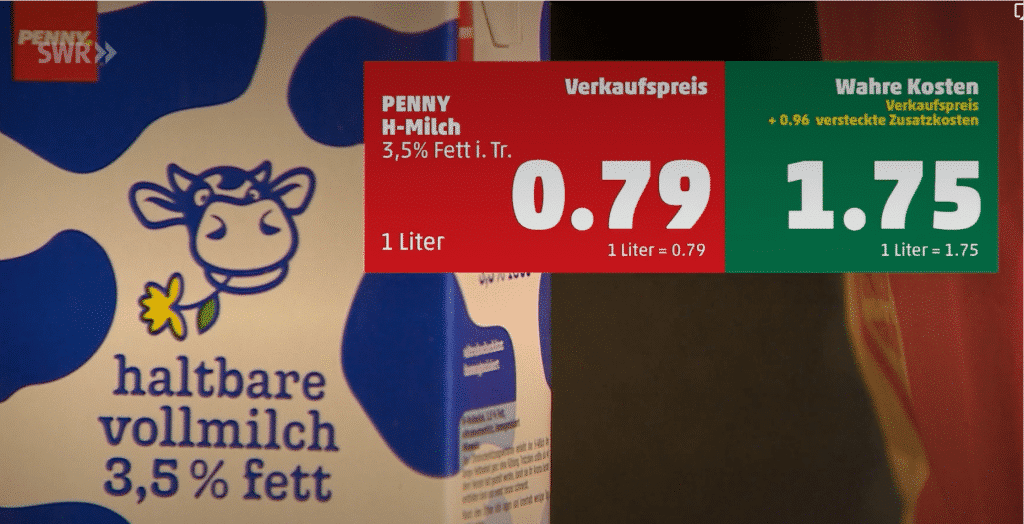

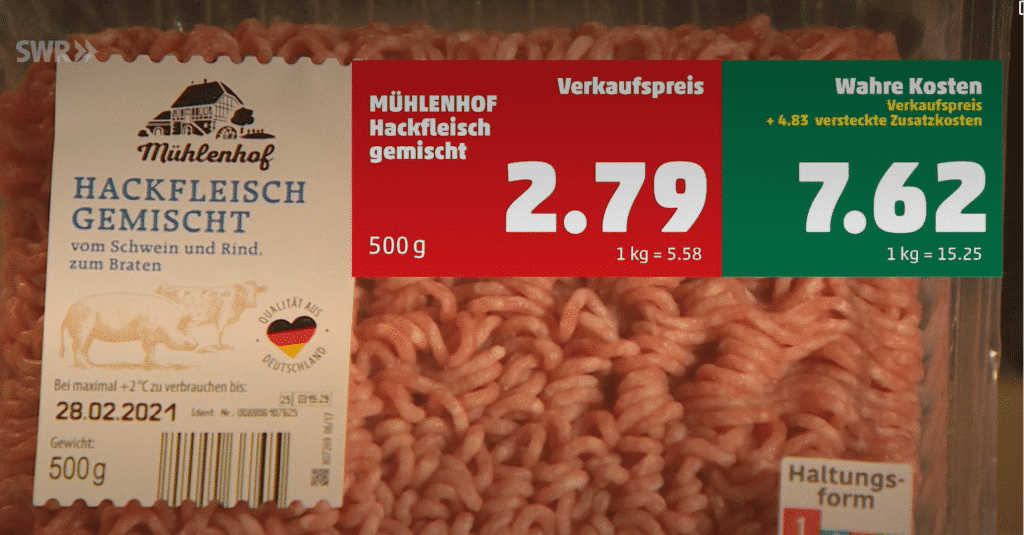

The supermarket chain Penny has entered the awareness battle with its consumers and put two prices on the packaging: the price one pays now, but also the price calculated based on so-called “true cost accounting”. These are invisible side costs, which are not paid now, added to the retail price (see figs 1 and 2). Differences in price reflect the costs actually paid by society as a whole, or the taxpayer.

Shift on to next generations

In recent decades, awareness of the differences between short- and long-term effects has grown enormously. This was prompted by pioneers like Rachel Carson, who wrote about the death of insects and birds due to pesticide use (Silent Spring). Birds of prey died as top predators in the food chain as pesticides (DDT, Dieldrin, Aldrin) accumulated in their bodies. Since our awareness of CO2 and CH4 (carbon dioxide and methane gas), we look very differently at cows, which make an additional contribution to global warming via methane. Are we doing the right thing if we want to keep so many cows, use dairy products and eat meat? Since Meino Smit defended his dissertation in 2018 on sustainability and the use of fossil energy in agriculture versus food (energy) production, you look at intensification, automation and labour emissions from agriculture with very different eyes. It feels strange, after all, that we have created an agriculture that uses as much fossil energy as it produces in food energy. Since Greta Thunberg, you do look very differently at politics, which constantly pushes the hot issues to future generations and just wants to leave solutions to the market or to tussling between parties. Meanwhile, we have ceilings in our mind such as a maximum 1½o C temperature rise in our atmosphere, while at the same time wondering whether this is all feasible by 2030, 2035 or even 2050. Electrifying society must become the solution without asking ourselves what the impact of new technology, batteries, rare metals and geopolitical implications will be.

Huge diversions arise in all discussions, prompted by those who make big money from the whole way of life. Is it all true about the climate? Are the models and calculations used OK? Of course, the tobacco industry wants you to keep smoking, Volkswagen and Audi want you to drive their cars as long as possible, the dairy industry wants you to keep consuming, but with a better life label, just like the pork and chicken industry will do everything they can to provide technical solutions so that you don’t have to eat a pound less of meat and an egg less. But will we safe the planet with this?

The cost of roll off

Penny shows its customers that a carton of UHT milk does not cost 0.79 cents but 1.75€. A pound of half-and-half (beef/pig) mince does not cost 2.79€ but 7.62€. The social costs of dairy and meat come off somewhat better as organic products, but the social costs of animal production are huge. Dairy, cheese, butter, and meat are actually luxury products. There is all sorts of things included in the social costs: land use, pesticides, groundwater quality, humus loss, food miles, energy use, but also animal welfare, antibiotic use, and even the cost of our diseases. In our increasingly ageing world, we are burdened with high costs of curbing our non communicable diseases: cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, type-2 diabetes, asthma and allergies, etc. Problems that were not present a hundred years ago and which have increased hand in hand with our Western lifestyle. In the TV broadcast, one of the interviewees spoke of the “errant of the 20th century”. All of us took the wrong direction and we donot stop running. Meat every day or three glasses of milk a day are really not necessary just as eating animal products is not a fundamental right.

How do we find solutions?

Solutions to the problems fall into the category of ‘consuming-less’ dairy and meat, a more or mostly plant-based diet, buying products from the region, products from animal-friendly livestock farming, such as in organic and biodynamic farming. If you look a little further, it is clear, that you produce in the most environmentally friendly way, when the product is made with little energy (raw milk), with few food miles (local to local), when the cows produce with the season (spring calving cattle), with little to no concentrate feed and certainly no soya. When it comes to animal welfare, calves-with-mother plays a role, a dignified life for each animal (keeping bulls up to 2 years), grazing cattle and space to lie in a straw bed, or on soft ground in winter. In the way you are spending your money, you can make a statement, and as a conscious consumer, you spend a lot of money to move agriculture in another direction. By now, the problem has become so obvious that the question is whether you can’t take agriculture in a different direction through government measures, different taxation and subsidies. With increased and reduced VAT rates, you can make products more or less attractive. Through other support measures, you can redirect agriculture in a different, environmentally and animal-friendly way.

It is careful then, that we don’t just substitute, a veg burger for a beef burger or an electric car for a petrol model or give a battery ‘a second life’. It is about real, fundamental choice to reduce.

What is holding it back?

It starts in the mind of consumers. Today, we want to be able to buy everything and spent a minimum amount of money for our food. In Germany, people spend on average only 12% of income on food and groceries. We consider a car, holidays, electronics and possessions more important than food. We find it normal, that our food does not increase in price, while the costs for the farmer, the processor and the shops do. In the mid-1980s, when the first dairy farmer in The Netherlands with over 100 cows wanted to convert to organic farming, his colleagues protested. Organic farms had an average of 30 cows in 1990 (Baars and Van Ham, 1995). Even in organic farming, we find it quite normal, that farms have increased their number of animals to more than 100 or 150 cows within one generation. It is even sadder for both the farmer and the animals. We don’t want to confronted with this, the animals are tucked away in large numbers in enclosed spaces and have a short, extremely boring life of eating and growing.

Industry and the food trade have a lot of power. Worldwide, there are only a handful of players who determine, what and how we eat. In Germany, there are still only four groups (Edeka, Rewe, Lidl and ALDI), which together control 85% of the food and dictate, what is on the shelf. In the Netherlands, we mainly deal with one milk processor (Friesland-Campina), which controls all milk flows, mainstream and organic. The same applies to Denmark or Scandinavia (Arla). Changes will not primarily come from such superpowers. Those are mainly concerned with their stock market value. It is often the small, local initiatives, where farmer and consumer can rediscover each other, so that you as a consumer can build a relationship again and know what the treatment of animals, the use of antibiotics or the food is really like. Only then, a value, a price, arises, where you as a consumer happily pay for the work and all the efforts for nature and welfare by the farmer. It may cost something, if again you know who or what you are paying for. Indeed: it should cost something!

Literature

- Baars T. and P.W.M. van Ham (1995). Diergeneeskunde en biologische veehouderij. Biologische veehouderij in Nederland, Tijdschrift voor Diergeneeskunde, 120, Aflevering 5.

- Smit, M. (2018). De duurzaamheid van de Nederlandse landbouw: 1950–2015–2040 (Doctoral dissertation, Wageningen University and Research).

Video

https://www.planet-wissen.de/video-was-unsere-lebensmittel-wirklich-kosten-100.html

Photo: a cow, with both its horns and tail removed for the sake of efficiency for humans