Take home message

- What is the deal with grass-fed milk? There are two aspects: the image of the sector and the health aspects for the cow (being outside, building vitamin D, grazing fresh grass) and for the consumer health due to the milk fat composition.

- Dealing with ‘grass-fed milk’ is a good example of when traditional more natural farming systems and consumer health go hand in hand.

In The Netherlands, the term ‘grass-fed milk’ may be used if the cows are allowed to graze at least 6 hours a day for at least 120 days. The main motive for this rule is the image of animal husbandry. The traditional grazing season varies from region to region and is mostly between April 1st and October 15th and lasts more than 200 days. There are countries, such as Ireland, Wales and New Zealand, where the cows graze over a longer period and thereby consume more grass. This is due to the favorable climate for a long season of grass growth based on relatively high winter temperatures and a consistent rainfall. Countries like New Zealand produce milk differently from America or Europe. Most farmers worldwide are fixated on the highest yield per cow. This led to the selection of really tall cows (wither height > 150 cm), such as the North-American Holstein-Friesian. These are skinny, high yielding cows that perform very well when fed a ratio with a high energy density, such as corn silage and concentrates from grains or byproducts from the food industry. In New Zealand their smaller cows are only fed grass. In New Zealand cows calve outside in spring, and they are fed only grass and graze until they are dried-off at the end of an almost 10-month grazing season. Grass is the cheapest roughage, and there is enough pasture due to the high rainfall. New Zealand cows can walk over 1½ hours to return from pasture to be milked, and then back to their pasture, twice a day. Concentrates are considered too expensive. Winter forage, as we know it in Europe as hay, maize, or silage, as well as stables to protect the cows in winter are hardly known.

Pasture genetics and grass-fed milk?

Thus, there is grass-fed milk in New Zealand, but it is a little different from grass-fed milk in Europe. European cows like the black or red Holstein or Brown Swiss cow have a different genetic background: tall and lean. These are cow breeds that no longer can be fed with only grass. The European dairy cow, which is genetically derived from the American dairy cow, produce too much milk and cannot cover their energy and nutrient needs through grass, and thereby they lose a lot of weight and have reduced fertility on a pure grass diet. Genetically, there are pasture cows and concentrate cows. Pasture cows are more muscular, smaller, and rounder and can produce milk from different qualities of pasture. In contrast, concentrate cows need their daily amount of energy from concentrated feed and maize silage, the main energy feed for the tall, lean high-performance cows (Fig. 1). Thus, most cows on pastures in Europe are supplemented with grain-based concentrates at the time of milking or in separate troughs on pastures.

Grass-fed milk is milk with a higher health value. This is based on the digestion of fresh grass and less corn silage and concentrates. The quality of the fat in the green, fast-growing grass contains chlorophyl and the fat from the green leaves is converted into a very favorable fatty acid composition, which consists of alpha-linolenic acid (n-3), conjugated linoleic acid (CLAs), branched-chain fatty acids and phytanic acid. Milk fat from fast-growing grass is yellow, not because of the yellow dandelions or yellow buttercups that cows feed on, but because of the high levels of beta-carotene. Winter butter is paler and harder, winter cheeses are also paler a bit more stiff and crumblier. Important markers in milk fat for a high intake of fresh grass are CLAc9t11 (rumenic acid) and its precursor C18:1t11 (Trans-Vaccenic acid), as well as a very good ratio of n6/n3 fatty acids in milk fat (around 1.0). When cows are fed winter forage made from corn silage, concentrates, grass silage or hay, these values drop dramatically.

Figure 1: Left: small, round, muscular cow type and right: tall, lean cow type

Does it make a difference whether a cow is really grazing outside or in the barn where she is offered cut, fresh grass? Grazing means that a cow walks around outside in the sun and can produce vitamin D3 through her skin, which we find in the milk fat. Vitamin D3 is one of the fat-soluble vitamins that are important for our health.

In for instance, New Zealand and Ireland, the concept of image and health from grass-fed cows overlap, and the concept of grass-fed milk coincides with a healthy fatty acid pattern. Low-input grass-based organic dairy farms can also produce a very good fatty acid pattern in the summer months. Unfortunately, grass-fed milk most sold in many countries today, comes from cows that are a) too little outdoors to get a high grass intake, sometimes only standing outside rather than grazing, and b) produce too much milk, forcing the farmer to provide additional high-energy concentrates around the milking times.

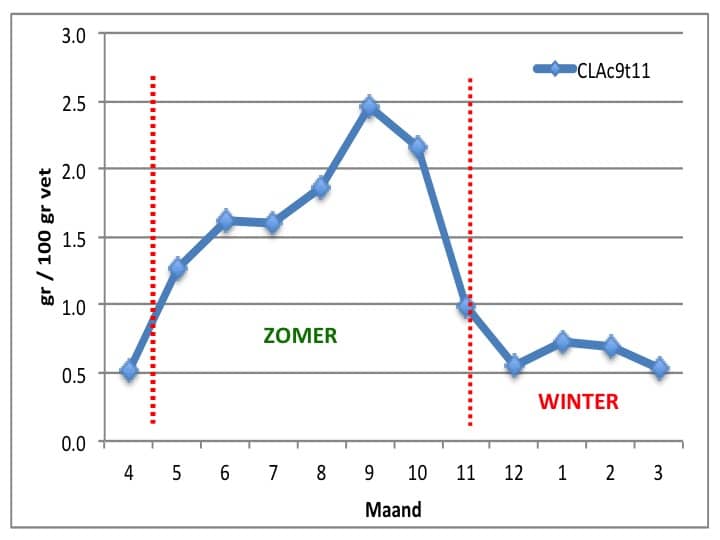

Figure 2. Course of the CLAc9t11 content in cow’s milk. Summer grazing and stall-fed forage in winter. In the summer period, fresh grass-clover is the main forage.

The graph (Fig. 2) shows the typical development of CLAc9t11. Samples were taken each month on a biodynamic farm 30 km in northern Germany. As soon as the cows got access to pasture mid-April, the CLA level increased monthly. At the end of summer there was a CLA peak, after the regrowth of grass and white clover after the summer drought. From October onwards, the cows were fed hay and housed and fed inside during the night. The samples taken from November onwards are a typical picture of ‘hay milk’. The CLA levels remain low and unchanged until the cows returned to pasture in the following year.

Harvesting the summer quality

How do you harvest the ‘summer quality’ of the pasturing and can you make this fat quality available in the winter? Farmers traditionally made cheese and butter from the summer surpluses. Summer cheese with its golden yellow color and soft consistency can be stored for months. The traditional farmhouse made Gouda cheese (in wheels of 20 kg) is specially made in September, the month when milk fat has the highest CLA content and there is a good fat/protein ratio in the cheese. Traditionally, summer butter was salted and kept in wooden vats, and nowadays we can also freeze summer butter and use it all winter.

Photo: Muscular cows of the traditional Black and White cows (Dutch Frisians or FH). Animals of this breed should not be confused with Holstein cows.